Gairdín Rós | Rose Garden by Vicky Smith - 8 March to 12 April 2026

8 March - 12 April 2026

Solo show:

Gairdín Rós | Rose Garden

Artist: Vicky Smith

Official Opening at 3:00pm on Sunday 8 March 2026,

Olivier Cornet Gallery, 3 Great Denmark Street, Dublin 1.

Olivier Cornet Gallery, 3 Great Denmark Street, Dublin 1.

Guest speaker:

Marysia Więckiewicz, Curator and Board Member of Interface Inagh.

Marysia Więckiewicz, Curator and Board Member of Interface Inagh.

The exhibition is accompanied by a text by Dr Phillina Sun, American writer based in the North West of Ireland.

The exhibition will also feature in our 3D virtual space.

The Olivier Cornet Gallery is delighted to present Gairdín Rós | Rose Garden, Vicky Smith's second solo exhibition with us.

The Night-Time of the Dandelions

Painted in the first four years of motherhood, Vicky Smith’s self-portraits explore a sense of self transformed by a time of intense change and adaptation to the needs of an entirely new human being. Until recently, mothers rarely featured as artists in paintings. Over the centuries in Europe, mothers have been portrayed according to the social values of the time, usually by men, shrouding the actual realities of mothers in myth and stereotype. Smith’s paintings draws on her lived experience as a mother, to reflect an image of motherhood as a state of mind that is not incompatible with creativity.

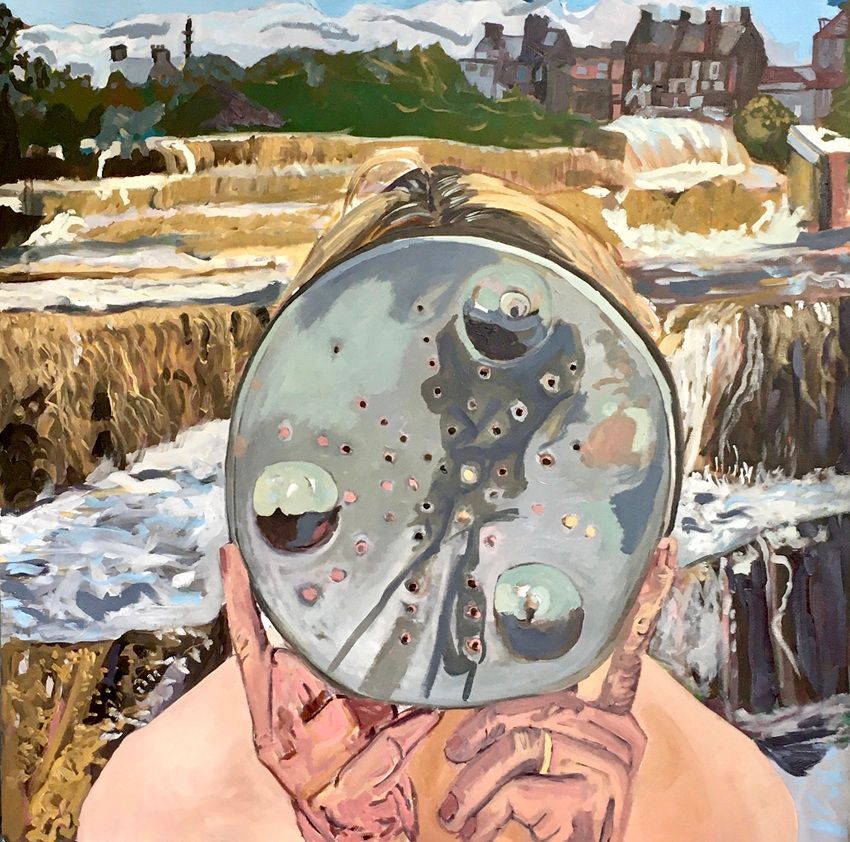

The most striking aspect of these self-portraits is the concealment of the face by an object. When viewing portraits, we tend to search first for the subject’s face. Often we assume the face reveals the personality or character of its bearer. “How can one not take an interest in faces, real or represented?” writes Laura Cumming on self-portraiture. “It is almost a test of human solidarity.”[1] Smith’s self-portraits present another test: how do we relate to the subject if we cannot regard the face? How may we glimpse an inkling of her innermost thoughts, ideas, and feelings? Since the subject is not instantly apparent, we must search for clues about her identity in the myriad details of the world in which she is presented.

The objects that conceal the artist’s face are domestic ones, useful items, not the medals, or jewels, or animals used to indicate status in conventional pre-twentieth-century portraits. Yet they function in the same way, conveying her place in the world, here as caregiver and homemaker, roles that are usually invisible, demoted by society as “women’s work”. In some paintings she holds up a colander or an iron or a beer sifter from a market in Botswana, where Smith lived for two years. In other, comically ambivalent paintings, her head is draped with a mop head or a lampshade, as if she’s been consumed by her domestic space. In another painting, her eyes peek through the handle of an iron, an implement Smith describes as “aggressive.” We are reminded that these ordinary, so easily ignored objects are implements, essential to homemaking’s intrinsic nature as a form of labour.

These domestic objects implicate the rituals of cooking, washing, mending, sweeping, and so on—all the countless forms of care a woman might perform in the home. Wielded like totems, they are given prominence, as if Smith is saying, “This is my world.” In place of her face, these objects might imply, then, the disappearance of the artist into motherhood. Looking at the work, I am reminded of the question that haunts women artists: “Is motherhood incompatible with art?” In the pursuit of her work, an artist-mother must confront the expectation that a mother should selflessly sacrifice her own desires for her child’s benefit. By making a series of works that centres the self, the artist-mother defies that expectation. The domestic objects, then, are no longer obstructions to self-actualisation. Rather the artist-mother might claim them as semi-ironic signifiers of the self, motherhood as an essential aspect of her creativity.

In Smith’s paintings, the artist-mother is ever the central figure, within landscapes that recall significant places in her life. Some backgrounds are recreated from inherited photographs, such as the golf course fringed by Scots pines, on which her father and grandfather played. In front of Ennistymon’s Cascades, Smith lifts a colander, now a shiny escutcheon to flourish in battle. The luminous hinterland of Connemara is rendered in gold and pink and mauve, in which Smith appears analogous to the mountain. One scene is dreamlike: the night-time of the dandelions; late at night, alone with one’s thoughts after a busy day minding a small child, seemingly insignificant things are magnified, immense, even lunar.

Flowers bloom, prodigious and refulgent; the world, or a woman, is a garden, fecund, teeming with potential. Gardens imply refuge, haven, paradise, where day-to-day worries fade away. Look closer: actual flowers are collaged into the paint, as if the surface is part- scrapbook. The paint, applied in thick, lively daubs, suggest a ken for great feeling. On every canvas, the female body endows her steadfast presence, protector and connector across generations and geographies. Seen in this way, the artist-mother figure in Smith’s paintings radiates power: always a mother, always an artist.

[1] Laura Cumming, A Face to the World: On Self-Portraits (HarperPress, 2009), p. 3.

Dr Phillina Sun